Dialogues about design and future

Documentation of previous Dialogues

Event: 1-Year Future Design Embassies – a celebration and presentation!

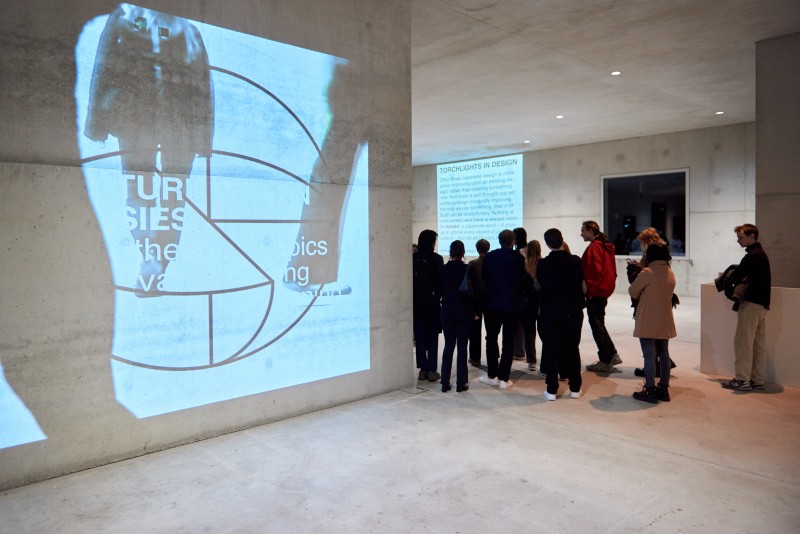

On November 2nd we celebrated “1 Year Future Design Embassies – International Students Ambassadors” with a big event at the Saana Building on the World Heritage Site, Zollverein. We, the embassy team of Folkwang University of the Arts, Karen Druebert, …

On November 2nd we celebrated “1 Year Future Design Embassies – International Students Ambassadors” with a big event at the Saana Building on the World Heritage Site, Zollverein. We, the embassy team of Folkwang University of the Arts, Karen Druebert, Celina Kroder, Lilli Seiler, Carl Vollmer, Alina Rogge and me staged an exhibition and a symposium on the whole first floor of the SANAA Building for many interested visitors to present everything we did in the one-year research project funded by the “Stiftung für Innovative Hochschullehre”.

The whole event was hybrid, so that our partners from RIT and its Vignelli Centre for Design Studies, our American Student Ambassadors Tayo Oke and Zaheer Shuyajee and many other interested guests could join in on the event from all over the world.

Our guests were greeted by an interactive projection with the most important quotes from our research (designed by Anastasija Delidova) and the “Embassy Secretary” sitting in a replica installation of our embassy office, including our two clocks with the two time zones from CET or Essen and EST for Rochester. There also was our relevant literature and photos of the activities in this past year on display.

The event featured exhibitions of the design of luminaires, resulting from the workshop “Light and Modularity, and a “Coffee + Dialogue” panel about the research question “Backtracking Modern Times. Are the ideas of Modernism sufficient to solve 21st Century problems?" Last but not least it culminated in the presentation of our research-by-design project “Torch:light – A Torch for Peace”.

One of the highlights of the afternoon was the presentation of the work of the International Student Ambassadors. Celina Kroder, Tayo Oke and Zaheer Shuyajee talked about their experiences as Ambassadors and about conducting a workshop for Design Graduate Students in the other country at the partner University. They talked about cultural differences and similarities, about their exchange on views and expectations on design in the 21st century and about their Workshop concepts of the Workshops “Light + Liminality” and “Light + Modularity”. Both topics were about light and centered around ideas of Modernism to make them comparable.

In “Light + Liminality” modernist designers of the 20th from Italy and the United States, Lella and Massimo Vignelli and Ingo Maurer representing a designer in the 20th century from Germany were reflected in terms of their philosophies and design processes and practices and then taken as models for the students design concepts, meeting the challenges of the 21st century.

In “Light + Modularity” the modernist concept of modularity, conceived for industry and mass-production, was analyzed and reflected by designing Urban Lighting concepts to support more sustainable production methods for the challenges of the 21st century such as energy crises, climate change and changing urban landscapes. This workshop was supported by Holm Giessler of the ERCO lighting company, a German producer of lighting systems for public applications all over the world with its Corporate Identity coined by the modernist Designer Otl Aicher.

The results of this workshop were exhibited during the event as 1:1 prototypes and were presented by the master students who had designed them. Due to the limited time of the event, the presentations were only very short so that the individual concepts and how those reflected the contents of the research topic “Backtracking Modern Times. Are the ideas of Modernism sufficient to solve 21st Century problems?" were perhaps not totally clear to the audience. Therefore, individual descriptions of each design will be found here in the archive soon.

After a coffee break in which the audience in presence as well as the online-audience (a camera was moved through the exhibition space) had the chance to view the exhibitions and after everyone was equipped with a coffee, the Panel discussion “Coffee + Dialogue” started, moderated by Student Ambassador Karen Druebert. For the panel we were happy to welcome prestigious guest experts, each representing various aspects of our research. These were:

• Prof. Josh Owen from the Vignelli Center of Design Studies RIT for TIMELESSNESS

• Prof. Alex Lobos, Director of the School of Design at RIT for INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE

• Prof. Martin Middelhauve from FH Dortmund for INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE

• Prof. Alexandra Martini from FH Potsdam for DESIGN METHODS

• Holm Giessler, Industrial Designer at ERCO GmbH for MODERNISM AND INDUSTRY (and today’s challenges)

• Prof, Sebastian Goldschmidtböing from KISD (Köln International School of Design) for MODERNISM + FUTURE

• Prof. Marion Digel from Folkwang University of the Arts for MODERNISM + FUTURE

The central question of our panel “Backtracking Modern Times. Are the ideas of Modernism sufficient to solve 21st Century problems?" was discussed from many perspectives:

The panel guests were aware of Modernism in Design as a culture of mostly western, mostly white and mostly male background. Yet, among others, it is still one major influence in design education and as such offers young designer’s criteria of what may be good design today. However, this shouldn’t happen without reflecting and questioning these critically and individually. OPENNESS and RESPECT for diverse perspectives and design solutions rooted in different cultures are central requirements for designing in changing societies. A very nice example here is the (loud)speaker design CHECHO by our panel participant Alex Lobos who used elements of Guatemalan signage and crafts to integrate this cultural heritage in a technological product. Within our diverse societies today, it seems more important than ever for designers to make sure that there are offers for anyone outside the respective dominating culture.

Yet the modernist notion of UNIVERSAL DESIGN or TIMELESSLESS may not be totally obsolete as panelist Josh Owen displayed with his impressive archeological sample of script on stone from thousands of years ago, comparing it to the shape of the object of a smart phone. Both objects were shaped to fit the human hand and the script was designed in a way that it was legible for its user. With this example he reminded us that there are unifying elements which define essential human needs and the shapes of human artifacts. The modernist ideas of finding unifying aspects and similarities may still be useful when designing in intercultural contexts.

For design students, modernist ideas can offer some orientation of what could be good design, rather than the contemporary impression, supported by Social Media that “anything goes”, which leaves them clueless sometimes. From modernist designers and thinkers such as the protagonists of the Bauhaus, the HFG Ulm and more specific from reading what Otl Aicher or the Vignelli’s wrote about the idealistic aims of their own work, we learned, that to them, the central quality of good design is the attempt of making a better world for as many people as possible. Maybe one of the most useful aspects which young designers can learn from Modernism today is its idealism!

The challenges in the 21ST. Century are very complex – Globalized economies, diminishing democracies, new wars, new tools such as AI, the global threat of climate change and more – all these are huge and complex challenges for young designers. And even our panel seems to have risen new questions – for instance nobody really knows how AI will develop in the near future, even though many of us are using its applications already in many ways and some designers have made first experiences using it for design.

Yet, maybe some of the modernists approaches and methods to create clarity and simplicity can be applied as models for a better understanding of the complexity of these big questions and challenges today. And maybe they can still help to find appropriate design solutions.

Concrete ideas and principles such as MODULARIZATION or MINIMALISM in design may still be useful concepts for design in the 21st century when it comes to finding more sustainable solutions designing within the global economy. ERCO for instance uses these principles to cover the very diverse demands of clients from all over the world, yet use a minimal number of parts to avoid production waist, to make the products easier to repair and to exchange their parts.

However, these principles stand for making the best within the system of consumerism instead of questioning the RELEVANCE of the product itself. This may be the responsibility of designers today more than ever. The RELEVANCE of new products needs to be evaluated in the light of the problem of Climate Change and fair distribution of goods. Young product designers today sometimes face the dilemma whether they should design at all. But there may be good reasons to design and spread a certain product and designers can be in the position to make sure, that it’s designed sensibly! As it would be the advice of Massimo and Lella Vignelli.

With our research-by-design project Torch:Light – a TORCH for PEACE, we tried to do just that – we wanted to design a product sensibly with a relevant purpose. The presentation of this torch was a very emotional and beautiful ending of our event. We chose the object of a torch for our design research because it is a highly emotional object which is loaded with many negative and positive meanings. What if we could design a torch with a positive meaning? What if we could design a TORCH for PEACE?

We decided to approach the topic by ways of a Modernist design process and wanted to produce as many torches as possible to make it accessible to as many people as possible. With the method of cast ceramics we were able to produce a limited edition of 60 pieces.

Read more about the design of a TORCH for PEACE and the torch research in the Logbook entry "A TORCH for PEACE".

COFFEE + DIALOGUE final panel

Welcome to our final COFFEE + DIALOGUE panel!

We have invited a variety of experts from the design field to discuss INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE, OPENNESS, TIMELESSNESS, INDUSTRY and the FUTURE - all within the framework of our research question:

Backtracking Modern Times. Are …

Welcome to our final COFFEE + DIALOGUE panel!

We have invited a variety of experts from the design field to discuss INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE, OPENNESS, TIMELESSNESS, INDUSTRY and the FUTURE - all within the framework of our research question:

Backtracking Modern Times. Are the ideas of Modernism sufficient to solve 21st Century problems?

Coffee + Dialogue Larry Corio, IDEO

Larry Corio is head of the field of “Impact Measurement”. (Design for Learning, Program Manager) at IDEO and in our session of Coffee + Dialogue we talked to him about “Measurement by Design” to learn more about practical research …

Larry Corio is head of the field of “Impact Measurement”. (Design for Learning, Program Manager) at IDEO and in our session of Coffee + Dialogue we talked to him about “Measurement by Design” to learn more about practical research methods and how to evaluate the impact of our design work. It was a great pleasure to have im!

First, Larry Corio gave us an introduction about IDEO and its development until today:

LC:

IDEO originally developed a reputation as a product design company in the 80ies and 90ies of the last century, located outside of Stanford in Silicon Valley. Founded by Product Designers and Engineers, it centered around a small microcosm of what Design is nowadays. It partnered with Apple and other organizations, for product design projects. In the last 20 to 25 years it expanded way beyond products, marketing its services of design related processes by coining the expression DESIGN THINKING. This qualified the design process for whatever it is – a product, a service or a concept.

In the last years IDEO dealt with topics such as AI, emerging technologies, sustainability, crime prevention, empathy design research, human centered design and the transformation of organizations, to make them “21st century ready”. This involved consulting and guiding people through cultural and behavioral change. Time spans of collaborations therefore went beyond 6 week- or 3 month-projects and rather changed into long time developments and partnerships.

The work in my current position in IMPACT MEASUREMENT at first glance doesn’t really seem Design related. However, in the last 5 or 10 years at IDEO we are thinking about how to be more responsible through design, so measuring the impact of what design can do makes a lot of sense and fits into that lane. Impact Measurement is becoming an important part of responsible and sustainable design.

MD: In our dialogues on what is responsible or relevant design we found it really hard to pinpoint the criteria for responsible design or design education. We found that there are so many different viewpoints, dimensions and aspects to consider, such as – politics, ecology, resources, economics, technology, power and culture etc.

So, when you go about impact measurement, how do you set the framework?

LC: I would like to share a few things about that –

Trying to do it all at once is not really useful. You will find that there is no singular system or process that will take care of all of those variables. So, really don’t focus on how to find the one ideal process, but on what is the balance you feel comfortable in striking. If you, for instance, stress economic criteria, you might be compromising the ethical ones. So, there is no ideal setting, it’s a judgement call.

Never do this in a vacuum for quick success. Never do it in a corner office but try to involve as many people as possible, engage users and clients in a discussion of what they think matters, as opposed to suggesting that you have the answer. So, it is about collaboration and participation.

Another important principal in a measurement process today is the principal of flexibility. In scientific measurement you change the variables to hold things constant. In an innovative design forward space, it is important that we create space for emergence, for things to happen, which we haven’t necessarily anticipated. Our aperture has to be flexible.

Principles of collaboration and flexibilities are what I would prioritize as opposed to trying to take into account everything there could be, setting up a framework for measuring the impact of a Design.

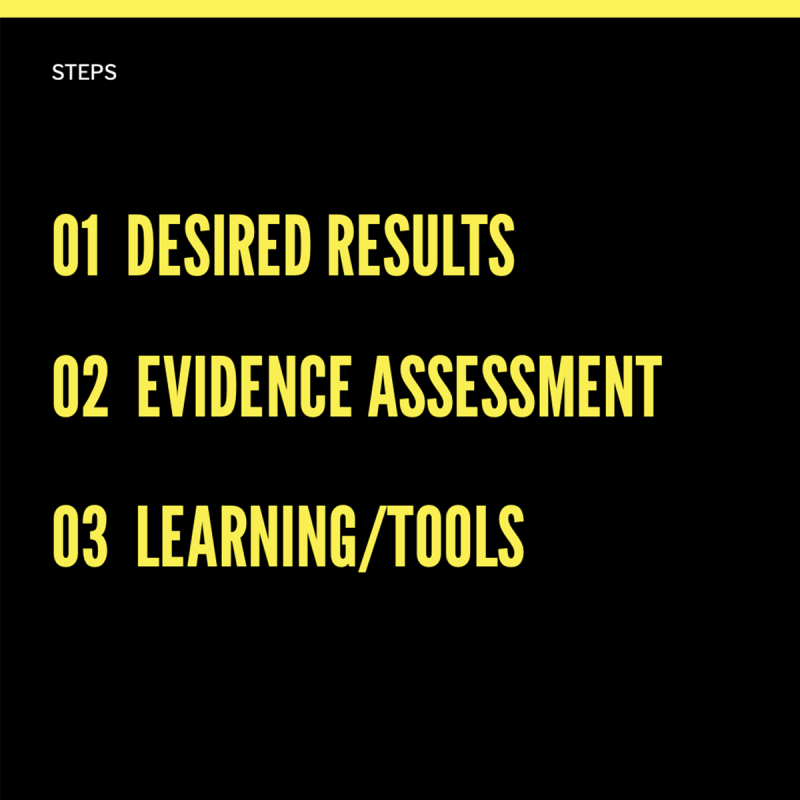

I would like to show you some of these principles: (He shares his screen)

Creative Tensions is a tool to grasp the mindset of the people you are dealing with.

It is a group activity – two sides of one topic are presented physically by standing on two sides of a line. Everyone has to decide on where they fall on that question. So, it’s not true or false, black or white, each person decides where they stand.

For Example: How do you make decisions, with intuition or evidence? –

There is no obvious answer to that and a person’s perspective may shift, depending on the arguments of the others. This question I use to inform my own practice. I always like to know from my clients in which way they are driven by these two powerful forces. It gives me the implications of how we could work together, whether there could be smooth or tense reactions to each other etc.

You can frontload this method when you’re working with any people to get your criteria. How do they prioritize issues such as sustainability, social equity etc.?

This can lead to a smoother conversation.

Assessment Standardized Tests are also something I would like to propose: As a former educator I am an ambassador for this. They are a new discipline to the design space and a challenge for myself: How do we create a wide space where measurement can flex as a practice?

I would like to give some examples for you as design students, design graduates, design teachers – What are the most important requirements for responsible design?

• flexibility

• relationships

• social responsibility

• imbalance

• prioritization of process over outcome (focus on the improvement of processes)

• interdisciplinarity (engaging with other disciplines, such as politics, industries, sciences etc.)

So, if designers should be flexible > then our measurement tools should also be flexible!

Here are examples of some measurement systems which are adaptive for designers:

The Rubric Game.

A tool to assess the quality of your team. It works like a Rubric Cube. (see MIT reference) https://playful.mit.edu/projects/metarubric/

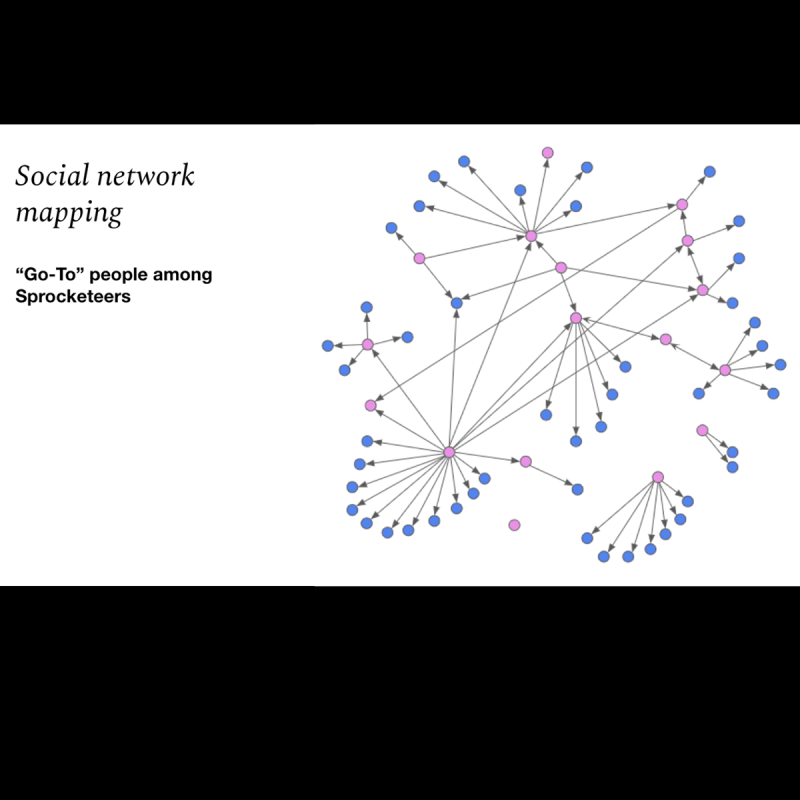

Social Network Mapping.

This tool can be used to assess the breadth and depth of relationships. Here the dots stand for people and the arrows show the direction of their interaction. This mapping tells you – who are the influencers in that network? In a group of trusting colleagues, you can keep track over time if you do this every half year.

Checklist of Behaviors.

Each number stands for a behavior identified in a group. This helps you to identify the signs for when a collaboration is working well.

Prediction Tool.

Here is an example of the New York times how the social background predicts kid’s outcome at college. You can see how income relates to career. If you track that over a long period of time these are not just estimations. This tool helps us predict how something could go. We can assert assumptions. So, for instance in the stock market or climate research we can use this method to assess the worst-case-scenario which again will influence the consequences. We can also surface things that didn’t go well.

Measurement by Design.

Last, I would like to show you how we can use Design to develop creative, interactive and adaptive measurement tools: For instance, IDEO designed this Laugh Detector. The light of this gets warmer the more laughter is in the room and colder the less. It immediately gives you feedback on the quality of your conversation.

Conversation:

MD

If you are proposing a measurement tool to be very flexible, then this is not as much about precision as about assessment of intangible matters, for which we as designers usually use our intuition.

LC

It’s probably a combination of those. It is important to maintain flexibility because in an innovative culture, things change and move quickly, so the suggestion to hold things constant, misses opportunities and thus must fail. However, precision is still important. There is no conversation about measurement without precise definitions. Even if what you are trying to assess is changing, you have to create a space of agreement, even if it is only momentarily. When designed well, your measurement plan creates moment of convergence which are essential to make design or project decisions. Decisions or agreements need to happen. Otherwise, all you are doing is observing. A well-designed measurement plan, creates moments of convergence, agreements, essential for making design decisions.

TO

Often foresight research seems to be very ambiguous. I guess, flexibility in measurement helps as well as teamwork, but how do you make sure to reach the right outcome or

foresight? And how important is this?

LC

At IDEO, clients come to us because foresight is one of our value propositions on the markets. Foresight scenarios can be inspiring, imaginative – however it is essential that in some cases of very future tentative thinking, we are brought back to earth by marketing tools. For instance, when we try to assess when is the appropriate time to release a product, it is mostly driven by the clients (adequate budget /political climate etc.) If we get it right in terms of the timing of release, it is often because our recommendations and the clients situation match. Foresight plays an important role it is both tactical but also inspirational.

MD

In past conversations we were talking about practical design as a research tool and design as a knowledge producing practice. Could design as a measurement tool help the processes in terms of sharing knowledge attained by design.

LC

Measurement is a practice. It shouldn’t just live at the end of a process and it shouldn’t just live, as in education, in the beginning, it shouldn’t be something we only do once. It is a process. It begins before a project (goals, who is involved etc.) Design research is a form of measurement to a degree. What you do to find out about what is important to your design and what not, those are all measurement decisions. Who do we include, who not. These things vary. Measurement is not the solution to everything but its principles are very extensive. Every time we change something in a process, that’s when measurement comes into the design process and helps to make decisions. Also, what is the end? How do we determine, what should be the end of the process? We try to build up measurement skills for our clients long beyond our project final.

MD

Karen, you are doing an evaluation of our Coffee + Dialogue practice in this research project. Do you use similar tools to establish the impact of that?

KD

The evaluation of our Coffee + Dialogue platform doesn’t use any such measurement tools. We do collect some data but there are no methods to really show the impact. The written evaluation that we make for our supporting organization, is the end. When it’s finished it is finished. It’s not about the process. There is no method that backtracks the process from the beginning or which includes talking to people. Again, it is not sufficient to see the true impact of our Coffee + Dialogues.

LC

It is good that you are collecting information. If you do this on a regular basis, it will allow you to create meaning. For instance, if you question how many people attended each session to which topics? To which time? To which guest? Those kind of questions may help you to improve the platform.

KD

But that’s not what I’m doing: The grant giving institution just wants more or less a documentation, it is just for us and just to do it, the theory around it is not for sharing.

LC

In our practice, every grant we received we were to report on. This was my first responsibility at IDEO to report on the grants to collect information and report back to the foundation. That was it. All we had to do was to report. But if you want to learn more about the impact of what you are doing, something you might do could be a quick conversation: “We have a hunch that this seems to be working, or people ask the most questions about this kind of topic, or maybe they are forecasting this…”. You should question those hunches, collect these types of questions and maybe talk to 5 or 6 attendees to see what they think, to see if they experience it the same way you did.

KD

My idea is to make an interview with someone working on the project. Yet, still I can’t measure the impact of the platform, because there is no long-term evaluation. So, how high can the quality of the evaluation be, if it happens only right after the practice?

LC

So maybe you can schedule this conversation 6 months after these practices.

Ask – “How does this former experience influence your future practice?” Hear from the attendees how the “Coffee + Dialogue” sessions, how these influenced them in their own work.

MD

Holm, do you at ERCO measure the impact of your lighting design in the process of development?

HG

Well not in such a deep way, we do of course measure how successful a product is.

Also, we have meetings after the process ends on how the process was, which difficulties we had, in order to avoid them the next time. We think a lot about the process of creating high quality luminaires. We get information from the market but not in such a deep way that we measure how users interact with our products. Maybe once the product is put into use, like in a museum for instance, we get feedback from the client. Each project has these feedback meetings but that is it. Larry, it is really interesting what you are proposing. At ERCO often the CEO comes and says we need this and that product and there is already a finished picture. Then we always have to ask: What is the problem? Those measurement methods you propose would help to achieve a more abstract and at the same time more precise framing.

MD

This leads me to my next question: It seems to be really essential to ask the right questions from the beginning. How do you find out which are the right questions and which tools do you develop for that, Larry.

LC

If you have a conversation with the user about the problem, I think you should make sure when you ask questions that you’re not leading the person whom you’re asking.

So, “What do you know about this product?” is a leading question because it assumes that somebody knows anything about the product. “What do you think about this product?” is a less leading question. It creates an opportunity for variety and less assumption.

How we phrase questions is important. Design research, when done well, allows us to leave open where the conversation goes and on part of the designer – we are not the driver but we follow up, we explore, we write stories, we guide rather than direct. In this way we might surface insights that improve the chances of success of a product or a service. There is no right or wrong and there is no truth. But there are ways to reach convergence. Consider – who even has these conversations? The leaders? Someone new to the topic? Ideally it should be somebody who doesn’t have an explicit relationship to the client. Even more useful are conversations you have at the end of the workday or the week. These usually surface quite valuable feedback. Early feedback is meaningful to people in a team, it shouldn’t come 6 months later.

MD

Larry thank you for giving us this introduction on measurement by design.

But I have one more question for you. We, the team of the Future Design Embassies are conducting a practical design research project. We are analyzing the Torch, a product loaded with many positive and negative connotations and many different emotions and meanings to different kind of people – It has been used for right wing rallies but also for the Olympics, as a symbol for freedom as well as for racism.

Now we are trying to design a peace torch: What does this torch have to be like? What kind of story does it have to tell? What kind of context does it have to live in? How can it get a positive connotation? A difficult problem, as we are experiencing. Maybe you have a suggestion of how can we re-direct the connotation of the torch in that way?

LC

To me the first thing that comes to mind is to ask: “Who’s in the room?” Talk to people who have benefitted from or have been disadvantaged by a torch. Invite them to be part of the process. My thought in this is, that our own experience is limited, so there may be others who have experienced this object more personally. Think about testing your prototypes and make a survey with the users. Consider the time and place of the testing because these factors influence the types of responses you may get. And it is most important, that it is a participatory process.

MD

Larry, thank you very much for all your great input! And we hope to talk to you again on our panel on November 2nd together with our other Coffee + Dialogue partners

COFFEE + DIALOGUE with Christian Schreckenberger about OPENNESS

OPENNESS is one of the values we explore in our FUTURE DESIGN EMBASSY in regard to its relevance for young designers when they are facing the challenges of the 21st century, especially when working in an intercultural context.

There …

OPENNESS is one of the values we explore in our FUTURE DESIGN EMBASSY in regard to its relevance for young designers when they are facing the challenges of the 21st century, especially when working in an intercultural context.

There are various contemporary ways we use the word OPENNESS when we talk about design:

- One of them is the open interpretation of the designed object by its user. The user is able to find his or her own applications when interacting with the object or product.

- The most common one is in the digital world where OPENNESS means the open access to information and knowledge. Design concepts, ideas or digital tools are accessible to everyone for free.

- The third way we use the word OPENNESS in the design context is the application of an open-ended process in which we don't know exactly where we're heading with our first impulses or ideas when we make explorations, being very open towards what we may find.

- Here at the Future Design Embassy OPENNESS is the attitude with which we try to face the world. We try to be open to otherness, to cultural differences and to everything we encounter when we leave our own safe spaces.

We invited Christian Schreckenberger to this COFFEE + DIALOGUE to introduce us to his interpretation of OPENNESS in his work as an artist and sculptor.

Christian Schreckenberger has brought some visuals of his own and of his student's work into the Embassy.

He starts his presentation with two pages full of small scribbles – drawings which communicate a search for form. The hand which draws the lines wants to explore, it’s a dialogue between head and hand. These scribbles document the process of drawing like discoveries you make when strolling along without any cause. The mind guiding the drawing hand is open to what it may find there. This is how Christian Schreckenberger goes about searching for the initial impulse for his work:

»What I mostly do, is with a kind of brainstorming under conditions of being half asleep and half awake. In a way I’m addicted to do that. It’s the first thing I do. Every time when I return to the studio, I pick up a piece of paper or better, not only one piece, mostly many pieces of paper and I start sketching and drawing. And then, at a certain point of time, some shapes and three-dimensional objects appear. And then I go on doing declinations, conjugations and variations of that object. After that I continue by treating the next image in the same way. And so on, and so on… they're all in a way similar but then they appear different on the page. This is what I do most of the time.«

Christian Schreckenberger then goes on to quote from the text that art historian Dr. Emanuel Mir has written about his work in 2014:

»Christian Schreckenberger's parallel universe is now filled with hundreds, if not thousands of objects. Few of these objects have manifested themselves in the three-dimensional world and the vast majority exists only as drawings. They either lay resting, awaiting their impending birth, or become eternally fossilised on paper like a failed species in a demanding environment. The designs which have been realised have taken all conceivable forms. They consist of a diverse range of materials and conjugate all textures, structures, materials and colours. They are ornaments, implements, fragments of quotations, gestures which have taken form or material experiments. Upon first glace it is only their heterogeneous, open character which connects them. (…) Every three-dimensional structure builds on a multitude of sketches, which consist of prototypes and variations of objects.«

Schreckenberger elaborates this process showing examples of several pieces.

- RUBBER DRAWING, 2021

- NO MORE EXCUSES No. 3, 2018

- ICON, 2012

- LOCAL GROUP, 2017

- CELIBRITY, 2021

- BIRD, 2022

RUBBER DRAWING and NO MORE EXCUSES are obviously extensions of the drawings into materiality. Both of them are featuring a line 'dancing' on a material surface. NO MORE EXCUSES is made from a found object, a piece of white chip board which used to be a part of a cabinet. The line 'dancing' on the surface was created by sawing the board into pieces and repeatedly assembling them at different angles. It's edges are chipped in the same way as the drilled holes which are left from the cabinets structure. The work is an expression of the open process of exploring and finding.

ICON and LOCAL GROUP are both depictions of spiral structures – explorations of the spiral in space. Whereas ICON is a velvet carpet with a very three-dimensional appearance, LOCAL GROUP is a large sculpture made from Styrofoam. The choice of material for LOCAL GROUP may be a practical, less costly solution but it also surprises as a contrast to the spirituality of the Palermo monastery in which it is situated. At the same time the spiral elements seem to be a quotation of the courtyard’s columns. The piece is an open interaction with the space it was made for.

CELIBRITY, also a piece made from Styrofoam, shows its sculptural complexity by spiraling the extrusion of a star. You can literally feel the open search for just the 'right' form in it's dynamic. Our embassy team, collaborating with an American design faculty, also discovers assets of superhero comics and an ironic glorification of stars and stripes.

The title BIRD lends an ironic note to the large sculpture of light blue painted panels, reminiscent more of a crashed airplane than a free-flying animal. In a way it tells an Icarus story. However, this may be only one interpretation of this work, which through its abstract form opens the imagination of the viewer to many stories.

With images of his student's work Christian Schreckenberger elaborates how he tries to open his student's mind towards finding their own topics and towards open-ended approaches. He encourages them to deconstruct objects and their functions in order to find new functions or aims for their own practice. In the same way he helps them to deconstruct concepts and opinions. He means deconstruction in the very best sense of trying to free oneself of stereotypes, of stereotypical behavior and simple stereotypical ideas of how things ought or seem to be. He describes himself as a 'birth helper' for this kind of approaches or ideas. He encourages students to try out various things, to try to understand them and to observe what could happen next.

In the end, Christian Schreckenberger sums up his working process like this:

»… and then things will develop. OPENNESS means not having a clear plan, perhaps you could call this a method of discovery. It's like going into the jungle and not following the straight path, but going to the left and to the right, to discover what is behind bushes and the trees – simply like this – this is what I mean by OPENNESS!«

After the presentation follows a Q and A session.

This is an exerpt of the most important dialogues:

Q: How do you know what to do next, or what is right, in this open 'method' of discovery?

A: I analyze the process, it has very much to do with being open for, failures, for mistakes, for experiments, for unexpected things and analyzing them as you are going along. Let me give you an example: If you want to be a chef, I mean a cook, a famous chef, what are you going to do? You won't start with reading recipes. This is not the first thing that you are going to do. You will start to boil an egg. I think this is useful. The very first thing that you do is to boil an egg. And the next thing you do is, look at what your mother does. And you should put your nose in every pot and smell – ah, this is chocolate, and how does it taste? And hard beans….etc. Wonderful. How can ingredients be combined? And then, when you finally have experience, this is the background you need to be able to understand recipes, not before that. As a teacher I try to avoid that students believe they can learn recipes and then just follow them, and then it'll be successful. If you've never boiled an egg, you won't be able to follow any recipes. And if you've never experienced the smell of beans, you won't understand anything about cooking, this is what I believe.

So, this example shows how simple things in life can be. I'm often wondering about very complex concepts, which students confront me with. Then I ask them “Did you ever smell beans? Or did you ever cook an egg?” So, back to your original question, what I’m also saying is that experience gives us the tools for making the right decisions in the process and letting us know what to do.

Q: In the very beginning you said that you do drawings which seem to be the origin for all of your work. You said you do them in a half sleep, half awake, state of mind. So, my question is, is the consciousness, kind of an enemy for OPENNESS?

A: No. No, absolutely not. I think OPENNESS has to do with using all the tools you have, it has to do with sometimes being half asleep or something times being very concentrated, sometimes being very playful, and sometimes following concepts and sometimes taking a distance to see things from far away. Design has nothing to do with only following one clear plan. But it's the same as with singing or cooking, I think, or maybe I don't know, building cars or gardening. You need all of your possibilities, your senses and your brain, everything. We do experiments, but we talk about what we are doing and we analyze it. I want to invite people to go to the playground, let's say, take sand forms and/or go into the kitchen, smell the beans and so on; but consciousness is just as necessary as daydreaming!

Q: I've been very regimented with my work thus far. I'm trying to be a little more open. You know, I usually go through very traditional design processes starting with sketch ideation and then kind of, just skip around a little bit and go back and forth from CAD and then back to sketch. I mean, generally I'm a little more traditionally regimented, but I'd like to find a freer approach.

I'm totally scared of this kind of process and I never took a course of yours. So, I try to figure out what helps you to decide which way you should go next after you made a drawing, and is there any big vision that you can say, okay, this kind of right, I can go now on to a physical model, etc.

A: You mean how to go on if nobody tells you the next step? I mean, in my course it's not that the people are really alone. If they have an idea, I will immediately show them examples. And you could try this, and you could try that. Imagine maybe it could work like this. This is very important. I expect that people arrive with an idea and some sketches and with some observations and some found footage or whatever. And if they offer that, then I'm like a catalyst. And then I have something which I can reinforce, but if there's nothing to reinforce, I can't reinforce it. So, this is the only point. There's no need to be frightened. OPENNESS doesn't mean you are alone all the time.

COFFEE + DIALOGUE with Steffen Siegel

It was a great pleasure today to have had Prof. Dr. Steffen Siegel as a guest for “Coffee + Dialogue” at the FUTURE DESIGN EMBASSY!

In preparation of our dialogue about “The relevance of the modernistic aesthetics in the photographic image …

It was a great pleasure today to have had Prof. Dr. Steffen Siegel as a guest for “Coffee + Dialogue” at the FUTURE DESIGN EMBASSY!

In preparation of our dialogue about “The relevance of the modernistic aesthetics in the photographic image of the 20th century towards social realities of the 21st century”, Steffen Siegel brought a series of images from the 20th and late 19th century as a base for discussion.

Steffen Siegel defined photography as part of the endeavor of Modernism, its characteristic aesthetics being most apparent in the time period from 1920-30.

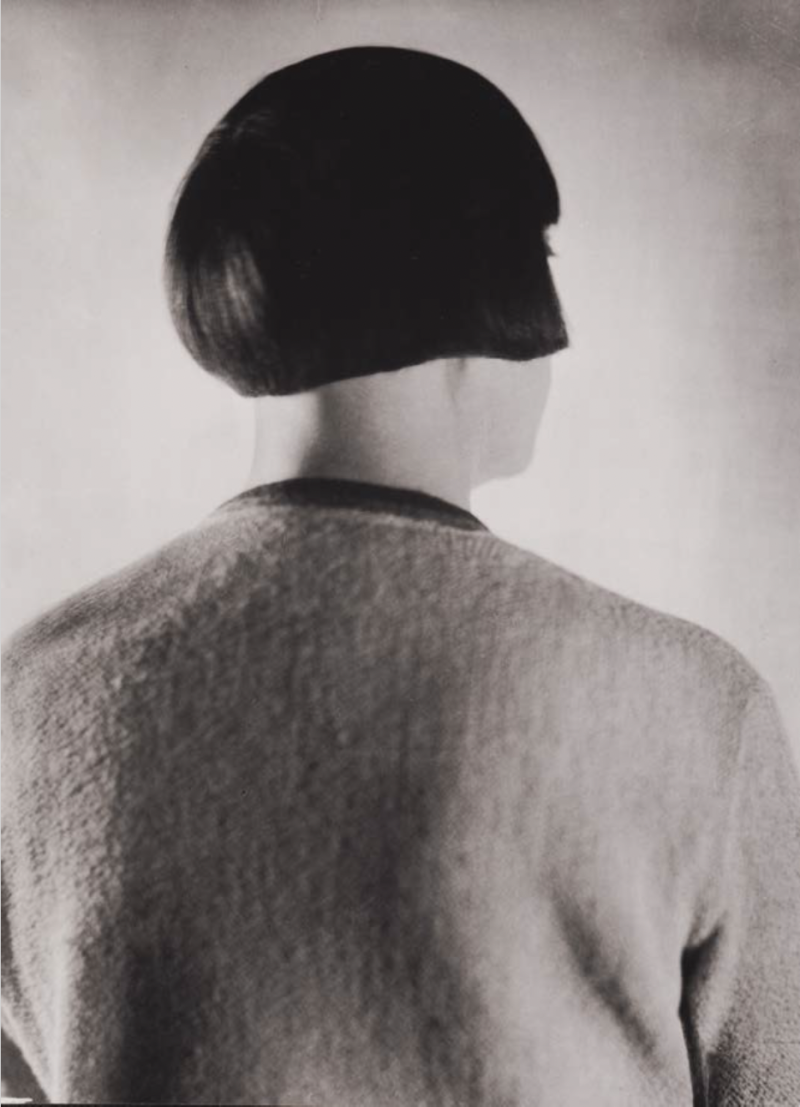

With the portrait of Asta Nielsen by Yva from 1930 and the selfportrait by Cahun Claude from 1928, he showed examples of how Modernism brought upon new aesthetics and new topics, such as “The New Woman” in the beginning of the 20th century. The portraits reflecting the new gender fluidity in those times. A key concept of Modernism in photography was the presence of women.

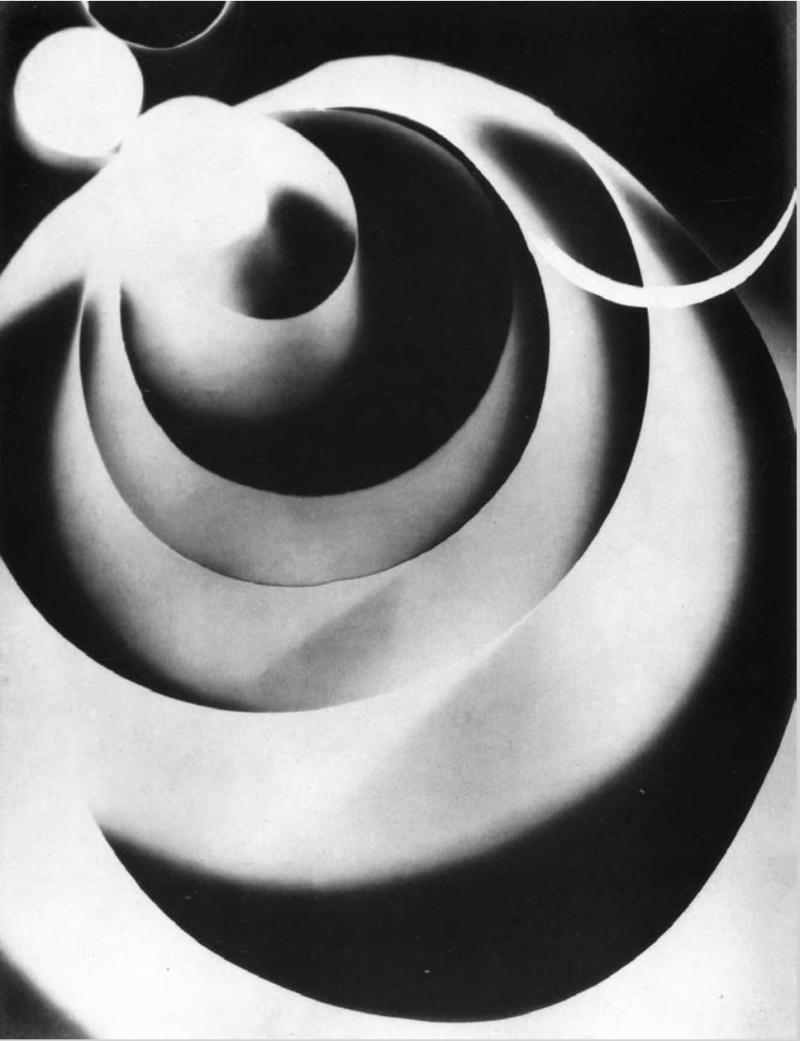

The photograms by László Moholy-Nagy & Lucia Moholy (double self portrait, 1923) and by Man Ray (Rayograms 5, 1922), showed that renewed techniques and experimental practices were central in modernistic photography at the time. Artists and photographers wanted to brake with traditional and classic conventions and thus produced a new, more abstract vision, the so called “The New Vision”.

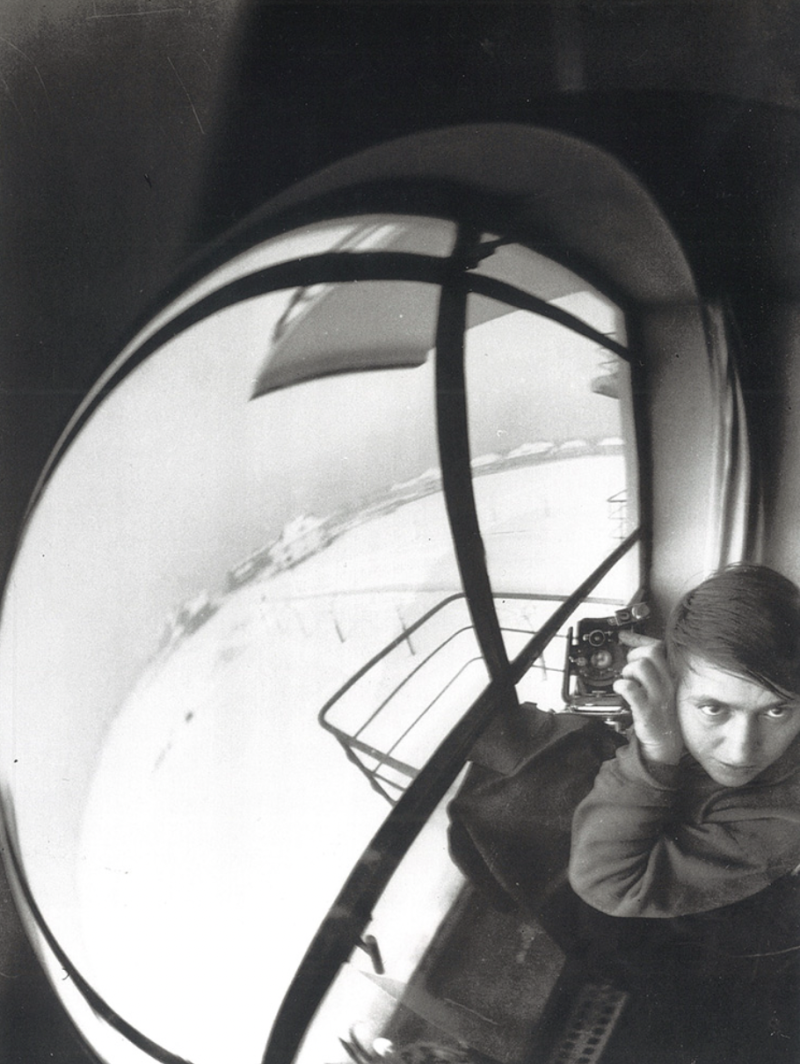

This new vision was characterized by aesthetic elements such as sharp angles or distortions as seen in the works of Alexander Rodtschenko (On the roof, 1932) and Marianne Brandt (self-portrait at the Bauhaus, 1929). Another key to Modernism in photography was how the photographic surface is rendered.

Modernism also entailed the search for objectivity, which is apparent in the works by Albert-Renger-Patzsch (The little tree, 1929) and August Sander. (High school student, 1928). They were practicing a new way to depict the world – New Objectivity. They aimed at a very specific way of establishing images by the means of the photographic body.

From today’s perspective the applied photography by Walter Peterhans was very artfull.

In his photograph of the glass-tea set by Wilhelm Wagenfeld in 1932, a new sense of sleekness and precision can be found, which perfectly matches the significance, which new technologies and minimalistic forms had in modern design at the time. A little later, in the mid-1930s Hein Gorny photographed erasers for PELIKAN, which he placed diagonally in a strict order in the layout of the photo.

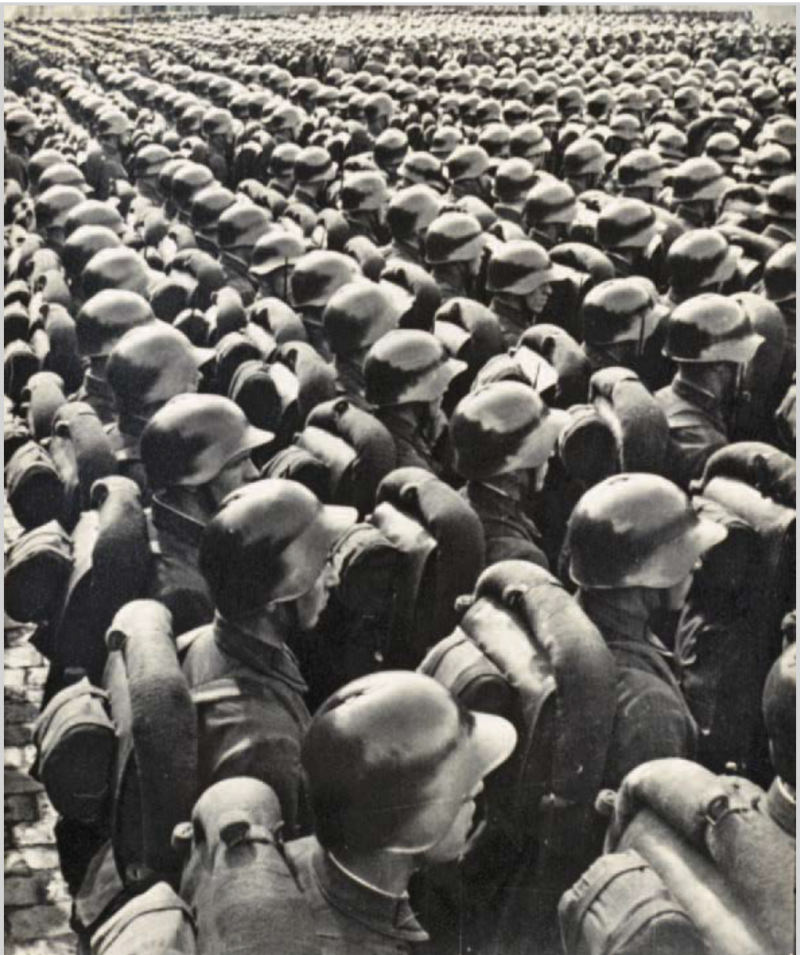

On the next page we see a very similar diagonal order in the photography by Georgij Petrussow in 1935, of soldiers standing in line, ready to go to war, used for the purpose of propaganda. This is something we cannot leave out when we talk about the aesthetics of Modernism. Another example for propaganda can be found in Willi Zielke’s photograph “Olympia” from 1936 in which he uses dramatic lighting and an upward view, as if looking at a statue, to produce a heroic vision of the young white male. Willi Zielke was the personal assistant of Leni Riefenstahl.

Modernistic photography also was subject to the question of its context, where does photography take place? With a photo depicting a news stand, Steffen Siegel makes clear, that modernistic photography was mainly distributed by the printed press and took place in printed forms as opposed to the medium of the internet, which coins our visual habits nowadays for the most part.

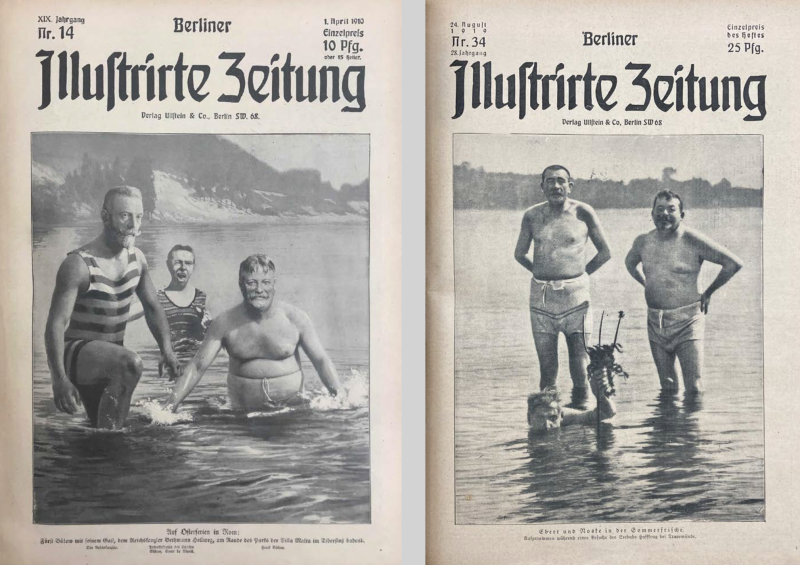

With a whole series of images from the “Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, beginning in 1910, Steffen Siegel shows how modernistic public images were already challenging us on what to believe and what not much earlier. In the first issue of April every year, the “April fool’s issue” the BIZ showed images in which the visual information was doctored, a mockery to test the eye of the audience. It raised questions to what can we trust or not? There were images manipulated as photomontages in a way that they show politicians either on top of a pedestal or in their bathing suites, as needed.

So, photography had impact on politics and still has today. Already in its early history it cannot be trusted to depict the “real world” or the truth. Already then, visual Information could be mockery or fake. This leads to the question which is central in the 21st century – What kind of visual data are we dealing with and how can we trust media? How can we deal with media when it comes to our understanding of the world?

After Steffen Siegel’s presentation follows a lively discussion with the student ambassadors in presence at the embassy and the people online who consisted of our student ambassadors from RIT, as well as scholars from other Universities as far as Indonesia.

In the discussion there was astonishment about how early on “the Fake” was present in media. In our times, the multiple imagery surrounding us all the time raises the question of how to deal with those reflections of what could be the truth. The difference being that, in 1910 the audience was a passive receiver of images, spread by an institution like a publisher of whom one knew who it was, whereas today everyone can produce and spread images according to one’s beliefs or means. So, we not only have to question the image but also the reliability of its source.

Then follows a comparison of Modernism in Photography and with Modernism in Product- or Industrial Design. There seem to be many similarities such as the breaking with tradition, the sleek and slim aesthetics, minimalism, a normative quality, etc.

Steffen Siegel points out that there was a “see-change moment” when Product Design left the medium of Photography, instead using CGI (Computer Generated Imagery) or CAD (Computer Aided Design, how designers call it). He asks whether it matters if a product is rendered by a computer, in comparison to the photographic image of the real object. How do product designers deal with that? Is it welcome, because you can easily make changes and variations for example in colors etc.? Today you can render everything and the results are hardly distinguishable from photographs.

Product designers use CAD for visual models quite often and they are experienced in deciphering those images. However, when one uses CAD models in presentations, the audience takes them for real, which raises the expectation that the proposed product will be exactly like it, which practically never happens. So, for designers, visual models can’t replace the analogue models which are needed for experiencing and testing proposed design solutions. It turns out that there is still more trust in photography than in the CGI or CAD images when it comes to product representation. Yet, this remains an open discussion.

With the impact of a war in Europe again, after many years of believing we wouldn’t need them anymore, the discussion comes to tanks. Tanks are products that have been designed and engineered. Steffen Siegel points out that the old ones still are working while the new ones with their high technology and computer programming are not. So, the modernist belief in salvation through technology and digital solutions comes short in this case.

Back to the question whether Modernism will still be relevant in 20 years from now, the participants of the discussion make observations that minimalism is making a comeback.The student ambassadors from RIT are reporting how they are looking into the work of Lella and Massimo Vignelli as representatives of Modernism and how they apply those ideas to their own work.

“Less is more” and similar claims may sound very shallow today, but when it comes to the production of machines that we buy in millions, less material means saving a lot of resources. Thus, Minimalism seems to be helpful in terms of a more environment friendly product design, not only because less resources are needed, but also in terms of representing a form of “Green Aesthetics” conveying psychologically that the product is more sustainable. So, can the impact of modern aesthetics lead to a more equitable design?

On the other hand, the efforts towards more sustainable design also leads to new aesthetics – DIY and 3D-Printing bring upon more individuality and forms, quite contrary to Modernism. Sebastian quotes from a book by Marion Poschmann: Marion Poschmann, Laubwerk, Verbrecherverlag (2021) with critical short texts. She is asking for something totally different than the modernist point of view: According to her, the world should romanticize again: “If we want to conserve nature to prevent an ecological catastrophe, we have to re-romanticize the world in our perception of nature.” (translation from German)

As a wrap-up of the discussion, Steffen Siegel recommends a publication, a primer for Art History from 1915, by Heinrich Wölfflin “Kunsthistorische Grundbegriffe“. (Wölfflin, Heinrich; Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe: das Problem der Stilentwickelung in der neueren Kunst; München, 1915)* Here, Wölfflin offers a scheme, which one can’t escape in its logic. He suggests that historically there were always two strands of aesthetics driving each other: One, which is classic, slim, timeless, minimal, etc. and another one which is baroque, flamboyant, decorated and very much overdone. These come in repeating waves.This should be of interest for designers in the 21st century and also forms of their combinations.

*for the English publication see "Sources"

COFFEE + DIALOGUE with Cordula Meier

MODERNE

Was ist die Moderne aus der Sicht der Designwissenschaft?

Ohne diesen aufklärerischen Moment in der Moderne, vor allem durch die HfG Ulm (1953-1968), an dem gesagt wurde, es muss soziologisch gedacht werden – heute nenne ich das designtheoretisch – hätte es …

MODERNE

Was ist die Moderne aus der Sicht der Designwissenschaft?

Ohne diesen aufklärerischen Moment in der Moderne, vor allem durch die HfG Ulm (1953-1968), an dem gesagt wurde, es muss soziologisch gedacht werden – heute nenne ich das designtheoretisch – hätte es ohne die Moderne gar nicht gegeben.

Die Antwort aus der Sicht der Designwissenschaft heißt: Die Moderne ist ihre Grundnahrung.

Sind die Ideen oder Grundsätze der Moderne noch heute gültig und inwiefern sind sie für Designer*innen relevant, wenn sie sich den Herausforderungen des 21. Jahrhunderts stellen wollen?

Für die Designlehre bedeutet das die Vermittlung von Zusammenhängen. Ich muss den Studierenden nicht mehr erzählen, was das Bauhaus ist. Grundsätzlich steht ihnen fulminantes Wissen im Internet bereit. Wichtig sind diese Zusammenhänge: Wie baut was aufeinander auf? Wie sind Verknüpfungsmomente? Das ist ja eigentlich nur noch das, was man lehren sollte. Ich finde es wichtig, dass man die Moderne kapiert, dass man die Theorien und Ideologien dieser Zeit versteht. Wie kommen die Modernist:innen dann zu einer Kaffeetasse oder zu einem Stuhl? Wie ist der Zusammenhang? Aber sicherlich kann man die Moderne heute nicht eins zu eins brauchen, sondern das muss irgendwie anders gehen.

Ich glaube aber, dass so eine Designgeschichte – und davon bin ich wirklich felsenfest überzeugt – die beste Kreativitätstechnik ist. Wenn man Phänomene aus der Designgeschichte kennt und sich aneignet, können aus verschiedenen Denktraditionen heraus Entwürfe entstehen: im aufklärerischen Sinne, im Sinne Focaults oder auch im Sinne der Postmoderne wie Memphis. Die Moderne als Kreativitätstechnik bietet einen Einstieg in den Entwurfsprozess.

Davon ausgehend, dass modernes Design Kriterien wie Angemessenheit, Minimalismus, Zeitlosigkeit, Funktionalität und den demokratischen Gedanken, dass Produkte für möglichst viele Menschen erschwinglich sein sollten, beinhaltet, sind diese Maßstäbe für das Design noch heute hilfreich?

Ich glaube, dass die Kriterien der Moderne als Ideologien und Theorien noch ganz hervorragend angewendet werden können. Das gilt allerdings nicht für die Ästhetik der Moderne wie sie sich damals gezeigt hat. Um eine Ästhetik im Sinne von Dampferarchitektur oder dem rechten Winkel Ulms, darum kann es heute gar nicht mehr gehen. Leute, die aufklärerisch denken, sagen, die Moderne ist heute zum Kitsch verkommen. Man guckt sich die Reihenhäuser an, die heute gebaut werden, die die Idee haben als seien sie Moderne Strukturen, aber in Wirklichkeit sind sie nur eckig und im rechten Winkel. Das ist eine Art verkommener Modernismus, der gar nicht mehr zu gebrauchen ist.

Im Rahmen dieser Projekt mit dem Vignelli Center for Design Studies sind wir bei den Vignellis, die deutliche Vertreter:innen der Moderne sind, immer wieder auf den Begriff der Timelessness gestoßen, der auch mit Formensprache zu tun hat, aber heute vielleicht anders interpretiert werden muss. Wie sehen Sie diesen Begriff als Designhistorikerin? Gibt es sowas überhaupt?

Diejenigen, die bei mir studieren, wissen ja, dass das Wort zeitlos bei mir verboten ist. Zeitlos ist verboten, denn es gibt kein Ding außerhalb der Zeit. Jedes Ding ist in seiner Zeit, jetzt in dem Moment, genauso wie jeder Mensch nur in seiner/ihrer Zeit ist und auch genauso sozialisiert worden ist. So ist auch diese Kaffeetasse zu ihrer Zeit – vor 10 Jahren oder in 20 Jahren hätte sie nicht so aussehen können.

Was viele mit Zeitlosigkeit meinen, ist, dass es über einen großen Zeitraum akzeptiert wird, beständig ist oder produziert wird. Also nicht kurzlebig, sondern langlebig. Also Zeitlosigkeit, ist vom Wortbegriff her falsch, denn die gibt es so nicht.

Objekte können zwar sehr langlebig sein, sind aber trotzdem immer nur in ihrer Zeit richtig, denn wenn sich die Energiesituation oder technische Errungenschaften entwickeln, verändern sich auch Objekte.

Die sogenannte Zeitlosigkeit in der Moderne oder die moderne Gestaltung bei Rams war ja immer verbunden mit etwas, das heute vielleicht als elegant interpretiert werden kann, aber damals nicht das vorrangige Ziel war. So sind diese formalistischen Ziele der Moderne nicht mehr notwendig, aber der Prozess zum Produkt, der Entwurfsprozess, der kann in einer ähnlichen Art und Weise sehr sinnvoll sein.

NACHHALTIGKEIT

Angesichts der Probleme des Klimawandels, des Bevölkerungswachstums, der schwindenden Ressourcen, der Zerstörung der natürlichen Lebensräume vieler Arten, ja sogar der Zerstörung unseres eigenen Lebensraums auf der Erde, stehen verantwortungsbewusste Designer*innen vor der Herausforderung, nachhaltige Lösungen für die Gegenwart und die Zukunft zu finden. Können die oben erwähnten Kriterien für modernes Design dabei ein hilfreicher Leitfaden sein?

Ich hab mich hier vielmehr gefragt, wie Designer:innen die richtigen Entscheidungen treffen können. Da sehe ich ein Riesenproblem. Welcher Ideologie, bezogen auf neue technische Visionen, glaubt man? Da die richtige Entscheidung zu treffen, ist schwerer denn je. Und das kann ein:e Designer:in nicht entscheiden, zumindest nicht alleine. Das Schöne an diesem Beruf ist, dass man sich von sehr vielen Fachleuten – und so würde das auch ein:e Modernist:in machen – Informationen einholt, um zu einer Erkenntnis im Entwurfsprozess zu kommen.

Wenn verschiedene Perspektiven eingenommen werden, kann eine aufklärerische Idee entstehen und sich daraus wiederum eine Form entwickeln.

ÄSTHETIK

Was bedeutet Ästhetik für Sie?

Ich begreife meine Seminare immer auch als ästhetische Erziehung. Um die Moderne zu verstehen, zeige ich sehr gerne Häuser, an denen die moderne Ästhetik abgelesen werden kann. Beispielsweise an Mies van der Rohes Farnsworth House (Illinois, 1945-1951).

Am Ende Frage ich dann: Wenn Sie sich ein Haus wünschen dürften, welches würden Sie nehmen?

Meine größte Enttäuschung ist immer, wenn sie Farnsworth House verneinen und sagen, es hat zu große Fenster, da kann ja jeder reingucken oder die freien Flächen seien kalt. Das ist für mich so ein Versagen, dass ich es nach zwei Stunden reden nicht geschafft habe, die wahnsinnige intellektuelle Größe dieses Hauses zu erklären, weil es durch seine Reduzierung auf das Wesentliche zu freiem Denken führt, dass dort zu sich und zum Eigentlichen gefunden werden kann.

Ich glaube, wir haben die Moderne, verknüpft mit freiem Denken, freiem Leben und mit dieser Ästhetik den Studierenden noch nicht erklären können.

Vor ein paar Jahren haben Sie in den Designwissenschaften ein Symposium organisiert, mit der Frage “Was denn das Schöne sei?” Inwiefern ist diese Frage angesichts der Herausforderungen des 21sten Jahrhunderts noch relevant für Designer*innen? Hat die Moderne in dieser Frage ihre Bedeutung angesichts der Herausforderungen des 21sten Jahrhunderts verloren?

Cordula Meier: Designer:innen müssen erklären können, warum was gut ist – und das nicht nur anhand funktionaler Eigenschaften. Die Ästhetik muss auch erklärt werden, aber wo liegen heute dafür die Merkmale? Die Moderne hat so einfache Kriterien geliefert in der Beziehung. Und jetzt sind die irgendwie zum Teil ad absurdum geführt, würde ich sagen. Wobei die Postmoderne, zu Beginn zumindest, genauso leichte Kriterien hatte: Es soll Spaß machen, es soll viel zitiert sein, die Lüge, die Ironie, alles soll integriert sein. Diese Kriterien sind ähnlich leicht umzusetzen, aber ich glaube, dass Ergebnisse im Design zur Zeit, gerade in dieser Zeit, diese wenig erfüllen.

Ich glaube schon, dass die modernen Herangehensweisen, wo sich aus der Ideologie heraus etwas darstellt, auch heute noch die richtige Wahl sind.

Marion Digel: Trotzdem hat die Postmoderne wichtige Einstellungen mitgebracht, wie z.B. „Es darf Spaß machen!“. Dass wir irgendwas gestalten, das einfach nur dafür da ist, Spaß zu machen, ist etwas, dass wir uns heute nach der Zeitenwende noch weniger trauen. Dabei ist dieser Aspekt der Postmoderne so wertvoll.

Cordula Meier: Natürlich, man möchte sie auf keinen Fall missen! Auch nicht als Reaktion auf diesen starren grauen rechteckigen Winkel Ulms.

In den letzten Jahren haben Konzepte wie DIY, BIOdesign und zirkuläres Design zusammen mit digitalen Produktionsmethoden wie 3D-Druck zu sehr diversen Formen von Ästhetik geführt. Ist in diesem Zusammenhang der Ästhetik-Begriff der Moderne noch hilfreich, um die Frage zu beantworten, was gutes Design sei? Und ist die Frage, was eine "elegante" Designlösung ausmacht, überhaupt noch von Interesse?

Schaut euch die ganzen Produkte von Apple an! Sie kommen in einer solchen reduzierten Ästhetik daher – von der Optik wirklich wie die alte Moderne. Obwohl ein biscchen pseudo elegant, aber immer noch sehr akzeptiert.

Welche Bedeutung hat die Ästhetik der Moderne für junge Designer*innen in der digitalen oder postindustriellen Gesellschaft?

Was ich mir als Stichwort dazu überlegt habe, ist die Autorenschaft. In der Moderne war es eigentlich so – obwohl Dieter Rams das bei Braun ganz anders gemachthat – dass die Designer:innen hinter diesem Funktionalem, Faktischen, hinter der jeweiligen Firma verschwinden. Es sollte das Hotelzimmer, das Automobil, den Stuhl geben und fertig. Und trotzdem war immer wieder ein Bedürfnis da, eine Autorenschaft, eine Signatur zu setzen. Ein Aspekt, der auch aktuelles Design betrifft, weil auf das Gestaltete anders geblickt wird. Ein gutes Beispiel dafür ist der Roman mit anonymer Autor:in. Eine Autor:innenlosigkeit, wie es in der Moderne gefordert, würde heißen, man liest den Roman und es steht nicht drauf: Rosamunde Pilcher. Wenn das nicht draufsteht, dann liest man den Text so anders, dann wartet man nicht auf den Mörder oder ein schlimmes Ereignis. Nein, aber wenn Rosamunde Pilcher draufsteht, weiß man die heiraten hinterher.

Die Rezeption ist eine so andere, wenn Dieter Rams drauf steht oder nicht. Die Autor:innenschaft finde ich eine wichtige Frage, auf die uns die Moderne keine Antwort gegeben hat.

COFFEE + DIALOGUE with Martin Middelhauve

It was a great pleasure to have Martin Middelhauve as a guest for our second Coffee + Dialogue session with the topic CULTURAL EXCHANGE.

Middelhauve who is a Professor for Object- and Roomdesign at the German FH Dortmund tells us, that …

It was a great pleasure to have Martin Middelhauve as a guest for our second Coffee + Dialogue session with the topic CULTURAL EXCHANGE.

Middelhauve who is a Professor for Object- and Roomdesign at the German FH Dortmund tells us, that as a teacher, he is pretty humble to explain the world and how to do stuff. “For me it’s more about asking questions and offering some tools to express the things the students are working on,” he lets us know.

As a designer and teacher he has a long history being part of IDEM, the International Design Experimental Meeting, a workshop based conference living international- and cultural exchange within the design disciplines since the early 90s.

Within his international experience, he was always more impressed from similarities than from differences, he tells us. “Design is an international language,” Martin Middelhauve states. He describes his experience of working on projects with other designers who couldn’t be more different to his own cultural background but when it came to the moment of designing together, within minutes there was a common base and a precise understanding of each other.

“If we talk about scenography and exhibition design, which always means to code and decode visual aspects of space, there are other expectations between different cultures, even if they seem pretty close at first,” Middelhauve explains. “Being sensitive and open to diversity is mandatory, always and especially within an international context.”

Martin Middelhauve is convinced that if you dare to laugh about yourself and the others – together, you have reached a point, which functions as a good base for creative work within an intercultural exchange.

Within our discussion on a whether the ideas of modernism are still being sufficient enough (or not) to potentially solve the problems of the 21st Century, Middelhauve believes that: “We are kind of stuck not just in our commercial- and product world. We are in a democracy-crisis, have to deal with climate change. Big things, that could perhaps evoke a kind of movement. We probably have to change really from the ground and not just continue to make the same products a little bit more sustainable, or buy organic milk, or drive electric cars,” the designer and teacher speculates.

Martin Middelhauve thinks that if you are a design teacher, you have really question what we are doing. One of the first questions he asks his students when they start their studies is: “What do you think, why I am paid for sitting here with you? Who's paying me and why? And this is a first step in questioning what is designed and what are we doing here and what is the function of all of that?,” he explains.

“Together with my students I like to doubt my own role as a design teacher, teaching them – to teach that you have to question your own role in design and in your function as a designer. And this is so multilayered, that you realize, there are no easy answers to nothing. The only thing that helps is to be really critical about it.” Martin Middelhauve points out.